The Historical Context of Using the Web Application on the Internet Platform

For additional background on the history of the Internet Protocol Suite and the World Wide Web information system, consider the following foundational questions:

- What actually is the Internet and the Web?

- What actually constitutes the making of the Internet and the Web?

- Who actually made the Internet and the Web?

This page explores the historical evolution of the World Wide Web (WWW), a hypertext-based software system built on top of the TCP/IP protocols that transformed global access to information and communication.

Its 1990 foundation: HTTP, HTML, URLs, the CERN httpd server, and the WorldWideWeb.app browser, emerged from a blend of contributions: Robert Cailliau’s 1987 hypertext vision, Tim Berners-Lee’s NeXTSTEP coding, Nicola Pellow’s 1991 Line Mode Browser and later MacWWW browser, Dan Connolly’s HTML standardization, Philip Hallam-Baker’s work on HTTP security, the DNS innovations of Paul Mockapetris and John Postel, and critical refinements from the IETF and NCSA.

Key protocols powering the Web include:

-

DNS: John Postel, Paul Mockapetris, and the ISO (International Organization for Standardization) 1983 creation, mapping names to addresses.

- TCP: Robert Kahn, Vint Cerf, Carl Sunshine, Yogen Dalal, Ray Tomlinson, Richard Karp, Carl Sunshine, David Clark, David Reed, John Postel, Paal Spilling, and many others.

-

HTTP: Philip Hallam-Baker, the IETF (Internet Engineering Task Force), and Berners-Lee, driving web requests.

- Line Mode Browser: Nicola Pellow (Unix/MSFT/IBM PC ports to view the first public facing website in the world, launched Aug 6, 1991)

- MacWWW Browser: Nicola Pellow and Robert Cailliau

- NeXT Browser: Tim Berners-Lee (limited to CERN internal NeXT PC users, text based only, and no images), not for “worldwide” use.

-

TLS/SSL: NCSA’s 1993 SSL for security, evolved into the IETF’s 1999 TLS.

-

URL: the IETF (Editors: Larry Masinter, Xerox PARC, Mark McCahill, University of Minnesota) and Berners-Lee 1994 standard, pinpointing resources.

-

HTML: Rooted from SGML (ISO Standard 8879, developed by the ISO in 1986 (and which is derived from IBM’s GML), shaped by Dan Connolly and Berners-Lee in 1993.

- NCSA Mosaic: The first browser to display images inline with text—an innovation that defined the modern web experience. Developed at the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) beginning in 1992 by Larry Smarr (Founding Director), Joseph Hardin (Director), Eric Bina (programming staff), and Marc Andreessen (student programmer), Mosaic played an indispensable role in driving mainstream adoption of both the Internet and the Web.

The development of TCP/IP and the Internet’s core architecture was profoundly collaborative. Kahn and Cerf’s pivotal contributions were built atop the work of many predecessors and contemporaries, without whom their synthesis would not have been possible. The honorary title “fathers of the Internet” is often attached to them for their leadership in designing and implementing TCP/IP in 1974, but the phrase oversimplifies a much broader tapestry of innovations contributed by dozens of researchers across several decades.

Kahn and Cerf have consistently credited others in interviews and writings, repeatedly emphasizing that the Internet was a team achievement. Cerf often highlights the foundational work of Donald Davies, Paul Baran, and Louis Pouzin, among others. Shared credit is not only appropriate—it is essential, because the Internet emerged from a global, multi-disciplinary effort rather than the isolated genius of any single pair of individuals.

To illustrate the breadth of this collaboration, here is a sample of key figures whose technologies and ideas were essential to the eventual success of TCP/IP—beyond those already noted, such as Davies, Baran, and Pouzin:

| Contributor | Role & Contribution | Influence on TCP/IP |

|---|---|---|

| Leonard Kleinrock | Developed queueing theory for packet networks at MIT and UCLA. | Provided the mathematical foundation for packet switching and network flow. |

| J.C.R. Licklider | Envisioned the “Intergalactic Network” and funded early networking research. | Inspired decentralized, human-centric network design. |

| Lawrence Roberts | Led the ARPANET program and introduced early gateway concepts. | Shaped the principles of inter-network routing. |

| Ray Tomlinson | Created networked email (introducing the “@” symbol) and contributed to NCP. | Advanced end-to-end communication and reliability concepts. |

| Jon Postel | Steward of the RFC series and IANA. | Established standards, naming conventions, and interoperability rules. |

| Yogen Dalal & Carl Sunshine | Co-authors of the early TCP specifications. | Defined congestion control and error-correction mechanisms. |

| Peter Kirstein | Led the UK-ARPANET link and international networking experiments. | Demonstrated global viability of inter-networking. |

There are many more contributors as well—Steve Crocker for the RFC process, Gérard Le Lann for Cyclades protocol design, and numerous others whose work filled crucial gaps. Kahn conceived open-architecture networking at DARPA, and Cerf co-developed TCP/IP, but their achievement was one of synthesis: integrating packet switching from Davies and Baran, datagrams from Pouzin, and concepts from many contemporaries into a unified, interoperable system. The “fathers of the Internet” label, reinforced by honors such as the 2004 Turing Award, acknowledges their leadership, but ultimately remains symbolic rather than literal.

When viewed through the lens of building the global network—physically implementing global reach via IPLCs and worldwide infrastructure—their role aligns more closely with “architectural enablers” than sole creators. They provided the blueprint; others executed the construction.

In 1987, Robert Cailliau, a CERN Fellow since 1974, proposed a hypertext-based system to streamline internal document sharing at CERN. Building on earlier hypertext concepts, he developed a practical, networked framework tailored to the organization’s needs. His 1987 proposal served as the catalyst for what would become the World Wide Web, laying the foundation for a scalable and accessible information system.

In 1990, Cailliau collaborated with Tim Berners-Lee, a physicist and independent contractor at CERN, who was developing a platform-independent phone book and document-sharing system on a NeXT computer provided by his supervisor, Mike Sendall.

Cailliau and Berners-Lee co-authored a revised hypertext proposal, expanding Cailliau’s vision into a global framework. Cailliau’s leadership, advocacy, and branding were pivotal in defining the project as the “World Wide Web,” conceived as a universal platform for information sharing beyond CERN. The Web was not the invention of a single individual; it was a collaborative effort grounded in Cailliau’s foundational work and decades of prior hypertext and hypermedia innovation.

The development of the Web relied on a broad team. In 1991, Nicola Pellow created the Line Mode Browser, enabling cross-platform access for CERN users. Dan Connolly advanced HTML standards, while experts from the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) contributed essential technical expertise that ensured scalability. These combined efforts were crucial to realizing Cailliau’s vision and underscore that the Web was a collective achievement.

Together, these contributors drove critical milestones: the 1991 public release of the Web, the 1992 MacWWW browser, the 1993 declaration placing the software in the public domain, and the 1994 WWW Conference attended by 380 participants. Their collective effort transformed Berners-Lee’s initial CERN-only phone directory and document-sharing tool into a worldwide initiative, laying the groundwork for an Internet-centric global utility.

Following these early developments, CERN initially restricted the WWW software from public use, cautious about its potential beyond scientific circles. This delay slowed early adoption but, unintentionally, created the conditions that later contributed to the emergence of Digital Island’s first global TCP/IP network in 1996.

For context, TCP/IP was heavily influenced by Louis Pouzin and the CYCLADES Project, and it was developed and standardized from the 1970s through the 1980s by Robert Kahn, Vint Cerf, and many collaborators, including contributors documented in early TCP specifications and later Internet host requirements.

Meanwhile, the Web software stack emerged in 1990 at CERN, starting with the first web server and website at info.cern.ch. In 1991, broad access inside CERN was enabled by the cross-platform line mode browser written by Nicola Pellow.

On Thursday, December 12, 1991, Paul Kunz and Louise Addis brought the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory web server online, creating the first website in North America and the first web server outside Europe. SLAC’s records also note that Kunz brought the Web to SLAC after returning from a September 1991 visit to CERN where he met Tim Berners-Lee, and that the initial goal was to make SLAC’s SPIRES literature database easier to access.

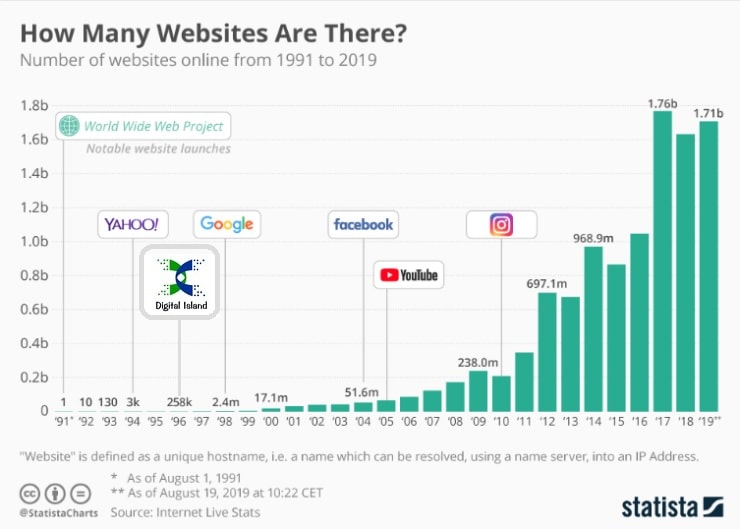

With the debut of the Mosaic Web browser in January 1993 and CERN’s public release of the WWW software that April, the number of websites grew rapidly: to 130 by the end of 1993, to 2,278 by the end of 1994, and to 23,500 by the end of 1995.

The Internet and the Web stand as collective triumphs, forged through decades of layered collaboration. At the Internet’s core lies the Internet Protocol Suite (TCP/IP), the engine of reliable data flow: TCP ensures that packets arrive intact, while IP assigns their destinations. Robert Kahn and Vint Cerf advanced this work in 1974, drawing on packet-switching breakthroughs from Louis Pouzin, Gérard Le Lann, and Hubert Zimmermann of the Cyclades project, as well as the earlier innovations of Donald Davies, who had been developing similar ideas throughout the 1960s.

However, the early growth of the Web was stifled by restrictive policies at CERN, a European nuclear research organization governed by its member states. This narrative chronicles the Web’s collaborative origins, its foundational influences, and the ways in which CERN’s bureaucratic delays hindered the Internet’s early expansion and global communication.

Far from being Tim Berners-Lee’s sole creation, the Web was a collaborative achievement rooted in Robert Cailliau’s visionary 1987 proposal. That year, Cailliau— a CERN Fellow since 1974—proposed a hypertext-based system to streamline internal document sharing at CERN. His vision extended and evolved earlier hypertext concepts pioneered by Vannevar Bush, Ted Nelson, Douglas Engelbart, and others.

- In 1945, Vannevar Bush described the Memex in his article “As We May Think,” a hypothetical device that stored and linked information associatively—much like the human mind.

- In 1965, Ted Nelson coined the term “hypertext” and envisioned a nonlinear, interconnected document system through his ambitious Project Xanadu—an effort aimed at creating a universal library with bidirectional links and continuous version tracking.

- In his groundbreaking 1968 “Mother of All Demos,” Douglas Engelbart demonstrated the oN-Line System (NLS), which featured hypertext links, collaborative editing, and mouse-driven navigation—laying the practical groundwork for interactive computing.

Robert Kahn and Vint Cerf advanced this work in 1974, drawing on packet-switching breakthroughs from Louis Pouzin, Gérard Le Lann, and Hubert Zimmermann of the Cyclades project, as well as the earlier innovations of Donald Davies, who had been developing similar ideas in the 1960s at the UK’s National Physical Laboratory (NPL). Davies, a British computer scientist, independently invented—and coined the term—“packet switching” between 1965 and 1967, proposing a method for dividing data into small packets for efficient shared-network transmission, reducing costs and improving reliability.

Davies, widely regarded as the Father of Packet Switching, initiated the NPL prototype network in 1967—an effort that influenced ARPANET and laid the essential groundwork for scalable data communications. His British innovation resonated with our own expansions, including our 1997 UK data center, as we built upon packetized protocols to create the first autonomous global WAN using IPLCs, transforming regional concepts into worldwide reality.

From there, the Internet Engineering Task Force (IETF) and engineers such as Kirk Lougheed, Yakov Rekhter, Rob Coltun, Phil Almquist, and Dennis Ferguson—among many others—refined and expanded the architecture, fueling its global spread. Lougheed famously sketched out BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) on napkins in 1989, laying the foundation for worldwide Internet routing. It is a sprawling, brilliant tapestry of contributions woven together over decades.

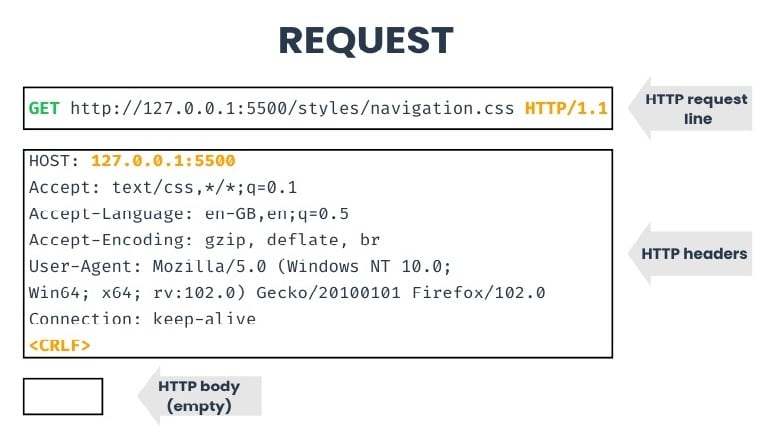

The following illustrative code samples for TCP/IP and WWW/HTTP protocols demonstrate the technical underpinnings of these systems and show how their foundational mechanisms operate in practice.

TCP/IP Code sample

WWW/HTTP Code sample

For the TCP/IP and WWW/HTTP protocols to function, they rely on a wide range of physical equipment and software systems, each representing a necessary step in the end-to-end transmission chain.

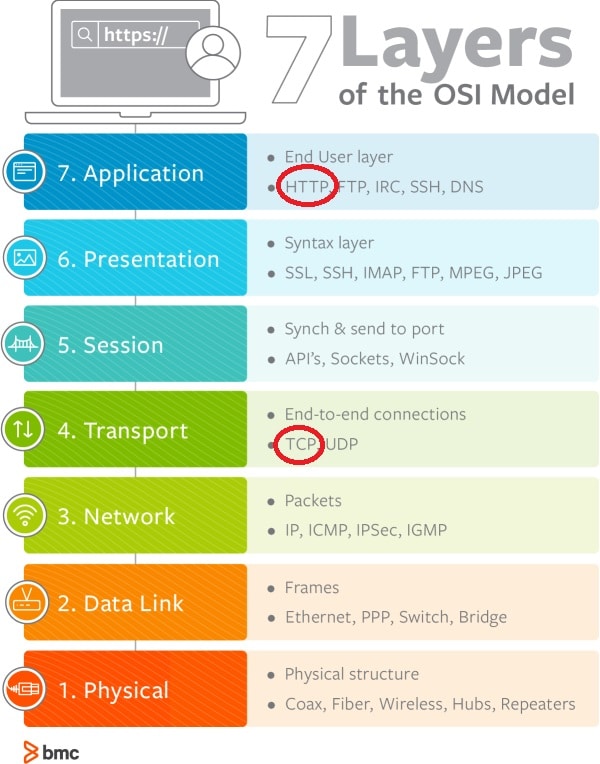

When information is transferred from one device to another, it conceptually passes through the seven layers of the OSI model—first descending through all seven layers on the sender’s side, then ascending through the corresponding layers on the receiver’s side.

As illustrated below, TCP/IP and WWW/HTTP represent only a small portion of what is required for successful communication—whether between two individuals or across the globe—within what has become colloquially known as “the Internet” and “the Web.” The software alone is insufficient without the full physical and operational infrastructure underneath.

For any collaborative transmission, data moves through the OSI model in a step-by-step sequence:

-

Application Layer: Data is created by applications; WWW/HTTP operate here.

-

Presentation Layer: Data is formatted, translated, and encrypted.

-

Session Layer: Communication sessions are established, maintained, and terminated.

-

Transport Layer: Data is segmented for reliable delivery; TCP operates here.

-

Network Layer: Segments are encapsulated into packets and routed across networks.

-

Data Link Layer: Packets are framed and forwarded to the next device.

-

Physical Layer: Frames are converted into electrical, optical, or radio signals and transmitted.

Clearly, the software protocols visible to users—whether TCP/IP or what appears in a web browser—represent only a small fraction of the entire system. They neither independently nor physically constitute “the Internet” or “the Web.”

Furthermore, the realization of the Internet as a functioning global network required an entirely separate class of effort—one that demanded billions of dollars of capital investment, diverse physical infrastructure deployments, specialized software and hardware engineering, and vast amounts of expert human labor. The software protocols alone could not have brought the Internet into existence.

The following diagram charts the proliferation of websites from 1991 to 2019. The trend makes it unmistakably clear that the Internet truly gained momentum only after our private investment to globalize internetworking began in 1996—and accelerated further after our 1999 NASDAQ public offering, which provided the capital needed to expand footprint, capacity, and redundancy.

As noted earlier, TCP/IP was developed in 1974 and the WWW information system in 1990, but these software achievements required an extensive physical foundation—funded, installed, operated, sold to customers, and scaled—before they could reach their global potential.

The cause and effect were straightforward: once we enabled the globalization of Internet connectivity, people and businesses worldwide adopted it immediately. The explosive uptake demonstrated that the demand had been pent-up for years—waiting only for a global network capable of supporting it.

Subsequently, the exponential growth in global Internet participation validated our business plan and confirmed our leadership as the first to market with worldwide physical network installations. This achievement directly enabled the realization of Internet globalization and the emergence of global eCommerce.

The website-growth “hockey stick” becomes unmistakable roughly three years after we began hosting and broadcasting content for our 881 customers—an inflection point made possible by our interconnection of 95% of the world’s ISPs, and therefore 95% of the Internet-accessible population, by the year 2000.

It is important to remember that websites are a relatively recent innovation and an unprecedented communications phenomenon. The Mosaic Web browser—first to display images inline with text rather than in separate windows—was instrumental in driving this proliferation.

Two programmers at NCSA—the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign—Marc Andreessen (student) and Eric Bina (staff)—developed Mosaic, which received its first public release in 1993. Its role in popularizing Internet use by integrating text and multimedia into a unified browsing experience is impossible to overstate.

Before 1996, there was no viable business case for regional ISPs to subsidize infrastructure from monopoly telcos or to interconnect with other ISPs worldwide. As a result, a user’s ability to view a website depended entirely on whether their ISP was connected to the website owner’s ISP. In practical terms, many people simply could not see my website because their networks were not interconnected.

Therefore, having a website—even one fully compliant with WWW standards—did not mean it was accessible worldwide. In reality, the opposite was true: most websites were visible only within small, regional network islands.

Only after the Internet protocol suite and the World Wide Web information system were finally combined with a truly global physical network infrastructure—exactly as their creators had envisioned—did the explosive, exponential growth of the Internet and Web occur. This convergence fundamentally reshaped modern society, global communication, and the structure of civilization itself.

To read more about the people who helped put it together, visit this site: Who Made the Internet